- France is unable to get its public finances under control. Prime Minister François Bayrou has failed to secure a majority for his austerity package and will now face a vote of confidence.

- Concerns about a sovereign debt crisis and a repeat of the euro crisis are already circulating. With a new fiscal architecture, the eurozone is better prepared for a debt crisis today than it was in 2010.

- In emergencies, the eurozone has always acted pragmatically and found ways to solve or postpone fiscal problems. This is likely to be the case if France slips into a debt crisis. Weak growth and higher inflation rates would be the negative side effects.

France’s public finances are back in the spotlight. Prime Minister Francois Bayrou has presented an ambitious austerity program to get the high budget deficits under control. In 2024, the deficit stood at 5.8% of GDP, and a deficit of 5.5% is expected for 2025. Bayrou failed to secure a majority in parliament for the austerity program, meaning he will face a vote of confidence on September 8.

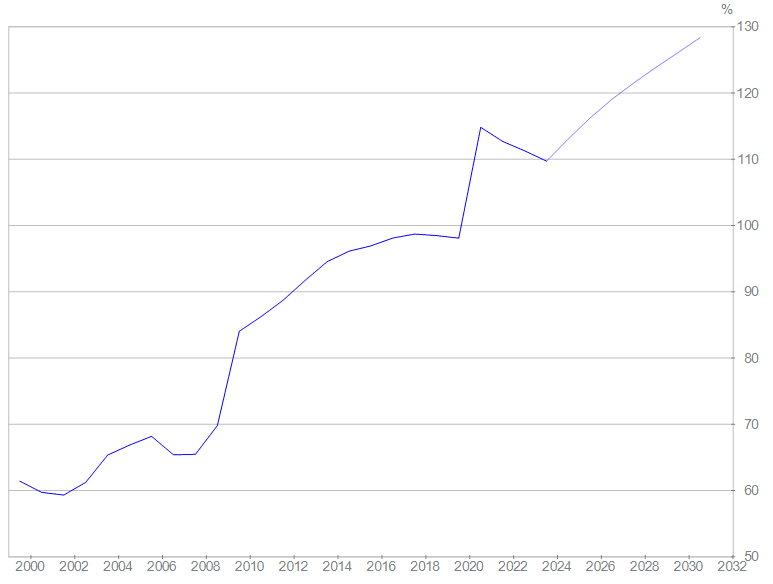

Given the fragmented party landscape and complicated majority situation, there are doubts as to whether budget consolidation can even be organized in France. If this is not achieved, the already high debt of around €3.3 trillion (114% of GDP) will continue to grow, and financial market participants will focus more intensively on the question of whether and at what price (interest rate) they are willing to finance French government debt.

Crisis management: new instruments

Against this backdrop, questions are already being asked about whether there is a threat of a repeat of the euro crisis. One thing is clear: the financial architecture of the monetary union has evolved since the euro crisis. With the establishment of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) in 2012 and new instruments at the European Central Bank (ECB), the monetary union now has effective crisis management tools at its disposal in an emergency, unlike in the past. If financial market participants lose confidence in French public finances, interest rates skyrocket and, in an extreme case, France even loses access to the capital market, this could spillover to other highly indebted eurozone countries. The monetary union would be shaken. To prevent such contagion effects, the ESM and the ECB would help France.

The ESM can grant loans to countries experiencing serious financial difficulties that threaten the stability of the entire monetary union. In return, the country concerned – in this case France – would have to accept a macroeconomic adjustment program involving structural economic reforms.

Since the ESM can provide a maximum of €500 billion in financial assistance, the funds may not be sufficient in the case of France. In contrast, the ECB can potentially provide support without limit. It has crisis management instruments ready for use in an emergency. Among other things, it could activate the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) it created in July 2022. The TPI “[…] can be activated to counter unwarranted, disorderly market developments if these pose a serious threat to the smooth transmission of monetary policy across the euro area. In such a case, the Eurosystem could purchase securities from individual countries in order to combat deteriorations in financing conditions not warranted by country-specific fundamentals […] Purchases are not restricted ex ante.” (Deutsche Bundesbank)

Like the ESM, the ECB also attaches conditions to any TPI assistance: countries whose government bonds the ECB is to purchase must pursue sound and sustainable fiscal and economic policies. These include: a) compliance with EU fiscal rules; b) the absence of serious macroeconomic imbalances; c) the sustainability of public finances; d) sound and sustainable economic policies.

Would the instruments be used in an emergency?

If we take the stated conditions at face value, it is highly questionable whether France meets them. In order to receive ESM aid, France would first have to accept economic and fiscal reforms that it has so far been unwilling to accept – otherwise it would not have ended up in such a precarious fiscal situation. It therefore remains to be seen whether the ESM could enforce the macroeconomic adjustment programs on the French government under pressure from the financial markets, which have so far been unenforceable. During the negotiations between the ESM and France, the situation on the financial markets is likely to be volatile.

France also does not meet the requirements for a TPI program. A glance at public finances alone shows that France is systematically violating fiscal rules. Both the budget deficits and the debt ratio have been well above the permissible levels for years, and the EU has opened an excessive deficit procedure against France.

Strictly speaking, therefore, the ECB should not help France within the framework of the TPI. One option for the ECB would be to protect the other member states of the monetary union from contagion effects and thus shield them from the French risk. But here, too, the situation is complicated, because Italy, the eurozone’s another economic heavyweight, is also heavily indebted and therefore potentially susceptible to contagion effects. Italy does not meet the requirements for a TPI program either, which means that the ECB would not be able to prevent Italy from being infected.

This means that the risk of a new euro crisis is actually high – were it not for the experience gained in interpreting the rules of monetary union when necessary. In cases of doubt, the rules have been interpreted (or adjusted where necessary) in the past in such a way as to enable assistance to be provided to an affected country. Monetary union was a political project from the outset, and its continued existence will probably continue to be ensured by political measures. In case of doubt, a bailout of highly indebted countries such as France would be organized by other eurozone countries or by the ECB. Although this contradicts the spirit of monetary union and the bailout ban that was originally put in place, pragmatism has long since prevailed. Now the citizens of the monetary union have to live with the side effects of this bailout pragmatism. In the long term, these are weaker economic growth and higher inflation.

France: Public debt as % of GDP

Source: IMF. From 2025 forecast.